Join us in celebrating Indigenous people and communities

Gathering and Sharing Stories

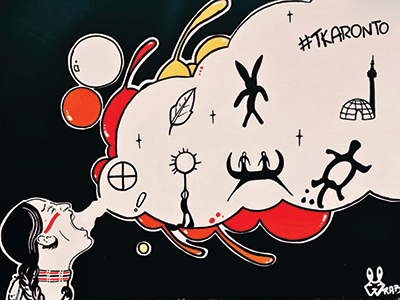

Tkaronto Where the Trees are standing in the water has been the site of human activity since time immemorial. The TTC acknowledges and celebrates the Indigenous Nations who are the original caretakers of these territories. First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples have continued to not only be caretakers to these territories we now call Toronto, but also have made invaluable contributions to place make and place keep. Indigenous peoples have supported the creation and building of this place we call home.

June

Ode’Miin Giizis

Strawberry Moon

This moon of creation, this moon is also known as Heart Berry Moon. This moon marks the beginning of summer, the longest day of the year and the harvest of the Strawberry in June.

The root word of Ode’Miin is Ode – Heart in Anishnaabemowin

The Strawberry resembles the shape and colour of the human heart and represents the sweetness and kindest of emotions that brings people together to love one another.

Dish with One Spoon Treaty

A treaty or agreement made between Three Nations: The Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee Confederacies and The Mississaugas. This treaty was made through the creation of a wampum belt that was exchanged to signify that each Nation was in agreement. This treaty was created to ensure that these three Nations were caretakers and protectors of the land known as the Dish (Great Lakes to Quebec to Lake Simcoe into the United States). There is only one dish which means everyone eats from the dish and reminds us that we need to share the dish freely. We all have a responsibility that the dish is never empty, cleaned and cared for. The dish is sometimes described as a beaver tail, which reminds us that we must be gentle with the dish and not use tools that might cut or damage the dish, such as a knife or fork. The use of the spoon signifies that we are being mindful of all that use the dish, and this represents peace.

As other Indigenous Nations, European settlers and all other Newcomers arrived to these territories, they have been invited to participate in this treaty of Peace, Friendship and Respect.

History of Indigenous History Month

In 2009 the House of Commons unanimously passed the motion declaring June as National Indigenous History Month. In June, all Canadians are encouraged to recognize, learn and participate in activities that celebrate and honour First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, understanding that Indigenous peoples are diverse and have many intersecting identities.

History of Indigenous Peoples’ Day

In 1986, Romeo LeBlanc, Governor General of Canada, announced the creation of National Aboriginal Day (now called National Indigenous Peoples Day) after many years of advocacy from various Indigenous groups.

- 1982: The Assembly of First Nations (Formerly called National Indian Brotherhood) called for the creation of National Aboriginal Solidarity Day

- 1995: Elijah Harper chaired a national conference for Indigenous and Non-indigenous people and called for a national holiday to celebrate the contributions of Indigenous peoples

- 1995: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommended the creation of National First Peoples Day

Sunrise Ceremony

This is a ceremony that many different First Nations peoples practice. This ceremony is about meeting the sun in the morning and starting the day with Mino Baamodziwin (That Good Way). First Nations peoples are giving thanks for all of creation and offering prayers. This ceremony is to start days that may be of importance or significance, such as Winter Solstice (December 22), Summer Solstice (June 21) and National Day of Truth and Reconciliation September (September 30).

Summer Solstice

Many Indigenous Nations celebrate the longest day of the year. The Summer Solstice marks new beginnings, new seasons, and is a time to set intentions. It is an opportunity to renew and move from past hardships and pain.

How to Support Indigenous Peoples

- Support – Attend Indigenous events

- Learn – Participate in educational opportunities

- Donate – Prioritize donating money to Indigenous organizations

- Shop – Ensure you are buying Indigenous items from Indigenous owned business

Translations

Canada – Kanata

Meaning “Village/Settlement” (Haudenosaunee)

Ontario – Kanadario

Meaning “Sparkling Water” (Haudenosaunee)

Toronto – Tkaronto

Meaning “Where the trees stand in the water” (Haudenosaunee)

Etobicoke – wahdobekaug

Meaning “place where the alders grow” (Algonquian)

Mississauga – misi-zaagiing

Meaning “Those at the Great River mouth” or Miswe-zaagiing

Meaning – “River of many mouths/outlets” (Anishnaabemowin

Mimico – omimeca

Meaning “resting place of wild pigeons” (Algonquian)

Spadina – ishpadinaa

Meaning “high place/ridge/sudden hill” (Anishnaabemowin)

June

Indigenous Peoples’ Month Events

June 18 – Na Me Res Traditional Pow Wow,

Fort York (250 Fort York Blvd.)

June 18–19 – Indigenous Arts Festival,

Fort York (250 Fort York Blvd.)

June 21 at 5:30 a.m. – National Indigenous Peoples Day Sunrise Ceremony

Nathan Philips Square (100 Queen St. West)

toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/festivals-events/indigenous-events-awards/national-indigenous-peoples-month

June 21 at 10 a.m. – 7 p.m. – Indigenous Day celebration: Free concert – Presented by Native Canadian Centre of Toronto,

Yonge-Dundas Square (21 Dundas Square)

June 21 at 8:00 – 10:30 p.m. – Indigenous Day Celebration: Concert and drone show – Presented by Native Canadian Centre of Toronto,

Ashbridges Bay Park (1561 Lake Shore Blvd. East)

ncct.on.ca

Toronto Public Library June events

torontopubliclibrary.ca/programs-and-classes/featured/indigenous-celebrations.jsp

Tkaronto Indigenous Peoples Portal

live.indigenousto.ca

City of Toronto Indigenous Affairs Office

toronto.ca/city-government/accessibility-human-rights/indigenous-affairs-office

Indigenous organizations

Shop

Native Canadian Centre of Toronto – The Cedar Basket – 16 Spadina Rd. (Spadina Station)

ncct.on.ca

Aanii Hello – Stakt Market – 28 Bathurst St.

(511 Bathurst streetcar)

aaniin.shop

Support

2 Spirit Peoples of the 1st Nations – Two locations – 145 Front St. East (504 King streetcar) and 2126 Danforth Ave. (Woodbine Station)

2spirits.org

Native Women’s Resource Centre – 191 Gerrard St. East (506 Carlton streetcar)

nwrct.ca

Na Me Res: Native Men’s Residence –

14 Vaughan Rd. (512 St Clair streetcar/7 Bathurst bus)

nameres.org

ENAGB – Indigenous Youth Agency – Two locations – 1005 Woodbine Ave. (Woodbine Station) and 1191 Weston Rd. (89 Weston bus)

enagb-iya.ca

Arts and entertainment

Native Earth Performing Arts – 585 Dundas St. East (505 Dundas streetcar)

nativeearth.ca

Vanessa Dion Fletcher

Lenape/Potawatomi

@vdionf

dionfletcher.com

Vanessa Dion Fletcher is a Lenape and Potawatomi neurodiverse Artist; her family is from Eelūnaapèewii Lahkèewiitt (displaced from Lenapehoking) and European settlers. She uses porcupine quills, Wampum belts, and menstrual blood to reveal the complexities of what defines a body physically and culturally. Reflecting on an Indigenous and gendered body with a neurodiverse mind, Dion Fletcher primarily works in performance, textiles and video.

She graduated from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2016 with an MFA in performance and a Bachelor of Fine Arts from York University in 2009. She has exhibited across Canada and the USA at Art Mur Montreal, Eastern Edge Gallery Newfoundland, The Queer Arts Festival Vancouver and the Satellite Art show in Miami. Her work is in the Indigenous Art Centre, Joan Flasch Artist Book Collection, Vtape, Seneca College, Global Affairs Canada and the Archives of American Art.

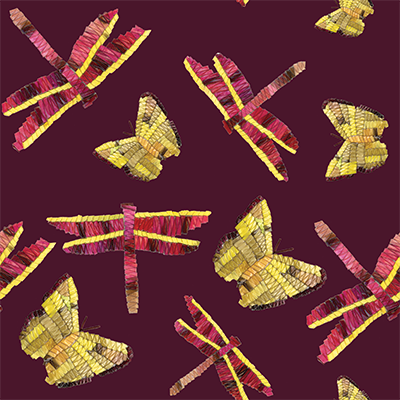

Butterflies and Dragonflies made from Porcupine Quills

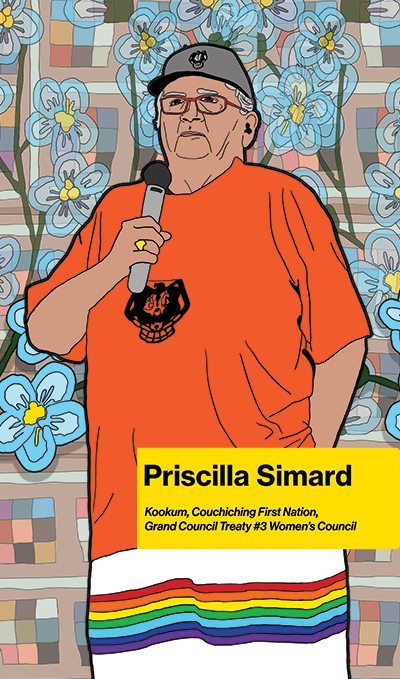

Fallon Simard

Anishinaabe

@contrarycompany

fallonsimard.com

Fallon Simard is an artist, educator and policy writer registered at Couchiching First Nation in Grand Council Treaty #3 Territory. He is an interdisciplinary artist, research fellow at the Yellowhead Institute, policy analyst at the Chiefs of Ontario, and owner of Contrary Company. His professional appointments enable research into multidisciplinary fields that both inform and draw from one another.

Portrait of Priscilla Simard Fallon’s KoKo (Grandmother): She is a survivor of residential school, Fallon wanted to honour his KoKo for her strength, courage and love.

Natalie Laura King

Anishinaabe (Algonquin)

@natalielauraking

natalielauraking.com

Natalie King is a queer interdisciplinary Anishinaabe (Algonquin) artist, facilitator and member of Timiskaming First Nation. King’s art practice ranges from video, painting, sculpture and installation as well as community engagement, curation and arts administration.

Often involving portrayals of queer femmes, King’s works are about embracing the ambiguity and multiplicities of identity within the Anishinaabe queer femme experience(s). King’s practice operates from a firmly critical, anti-colonial, non-oppressive, and future-bound perspective, reclaiming the realities of lived lives through frameworks of desire and survivance.

King’s recent exhibitions include Come and Get Your Love at Arsenal Contemporary, Toronto (2022), Proud Joy at Nuit Blanche Toronto (2022), Bursting with Love at Harbourfront Centre (2021) PAGEANT curated by Ryan Rice at Centre[3] in Hamilton (2021), and (Re)membering and (Re)imagining: the Joyous Star Peoples of Turtle Island at Hearth Garage (2021). King has extensive mural making practice that includes a permanent mural currently at the Art Gallery of Burlington. King holds a BFA in Drawing and Painting from OCAD University (2018). King is currently GalleryTPW’s 2023 Curatorial Research Fellow.

Miss Gay Ojibway – Is about survivance and desire, countering damage centered narratives that are tied to Indigenous communities and the conspicuous consumption of queer Indigenized trauma. I hope people leave with a sense of being seen with a sense of hope, and the ways in which futures can be built. It’s really about resistance and denying commodification of trauma and violence. It’s about transforming our relations and the things that we all as agents of colonialism and oppression (willingly and unwillingly) partake in, intervening at the level of governmentality. I’m trying to get the viewer to entangle themselves in the project of colonialism, through a queer lens that is focused on joy and pleasure. I would like people to leave with a sense of a world-building, pleasure-centred resistance, and joy. I’m really interested in that transformative aspect - the work I do is engaging with issues of representation, social interaction and social systems, and material access. Using art as a reconnection with culture, with land and with each other, is important, and being vulnerable or being willing to learn in public is challenging, especially in relation to investigating the effects colonization has had on my identity and being willing to share this. I make this work especially for my queer Indigenous kin in mind.

Like a Hawk Silently Soaring Over The Don Valley – King explores kinship systems with family and ancestors who have passed on, how their spirit is a part of us, and how when we silent the mind, we provide a door for them to communicate with us and the strengthening of relationship we still have with those people, how these relationships continue well beyond their existence in the physical plane. The sacred fire is a door to relations, we carry their memory with us.

Amanda Amour-Lynx

L’nu/Scottish 2Spirit

@amour.lynx @freelynxii_official

amour-lynx.art

Amanda Amour Lynx (they/she/nekm) is a Two Spirit, neurodivergent, urban L’nu

(Mi’kmaw)-Scottish interdisciplinary artist and facilitator currently living in Guelph,

Ontario. Lynx was born and grew up in Tiohtià:ke (Montreal) and is a member of

Wagmatcook FN. Their art making is a hybridity of traditional l’nuk approaches and contemporary painting with new media and digital arts, guided by the Mi’kmaq principles netukulimk (sustainability) and etuaptmumk (two-eyed seeing), Lynx’s artistic practice discusses land and relationality, environmental issues, navigating systems and societal structures, cultural and gender identity, (L’nui’smk) language resurgence, quantum and spiritual multiplicities. Their facilitation work focuses on designing community spaces committed to creating healthy Indigenous futurities, guided by lateral love, accessibility and world-building.

Amour-Lynx’s recent projects include Spark Indigenous (2023), a collaboration with Meta and Slow Studies Creative, an augmented reality creator accelerator that amplifies Indigenous cultural expression and storytelling through using emerging technology and AR. Virtual Beginner Two Spirit Regalia Making Skills (2021-2023) with Canadian Roots Exchange, a program for IndigiQueer, two spirit and LGBT+ youth, that provides access to regalia making workshops, genderfluid ceremonial teachings, pow wow culture and rooted in peer-led community and cultural practices. Their curatorial projects include 2S Digital Constellations (2023) a short project incubator and augmented reality virtual exhibit highlighting the works of emerging two spirit textile-based artists using new media, and Shapeshifters (2019) exhibit at Beaver Hall Gallery (Toronto) part of the annual Bi+ Arts Festival, which featured and highlighted the work of Two Spirit artists in dialogue with the Bi+ festival showcase. Their writing was published as part of grunt gallery’s Together Apart anthology (2020), and revue esse (2020). Lynx also worked as program assistant at Xpace Cultural Centre, a cultural programming hub and art gallery serving emerging artists (Toronto) from 2016-2018. Their artwork has been featured in gallery spaces, festivals and publications nationally.

Website: http://amour-lynx.art/

Instagram: @free_lynxii

Project Title: Nipniku’s - Basket on the Moon

Artist Statement Elaboration:

The title Basket on the Moon comes from cultural story written by L’nu educator and Mi’kmaw language teacher, Jasmine Johnson, Millbrook First Nation, NS, in dedication to young traditional basket weaver, Shanna Francis of Kisitaqn Basketry, Eskasoni FN.

This mural centers a basket design created by Francis, with the inclusive pride flag pouring onto the landscape that divides the artwork into night and day. The basket is positioned to the right of June’s full moon, Nipniku's, which translates to Trees Fully Leafed. The Mi’kmaw calendar, Tepknusetk, follows the lunar cycles and ecological happenings in L’nuekati’k (land territory of the Mi’kmaq, also traditionally known as Mi’kma’ki’k, spanning the Atlantic provinces of Canada) and highlights the cosmological and natural events observed geographically from the region. The juxtaposition of moon and basket creates a lunar eclipse, visually depicted by the two separate night and day skies, merging in the middle.

Likpenikn (basket weaving), is a traditional and ancestral practice of Mi’kmaq peoples, with intricate and involved workmanship passed down from generations through oral tradition. Weaving connects L’nuk to cosmology and ancestral stories of family, the land and an overall philosophy of being. It ties our people to a long entrepreneurial history of our peoples, creating our own livelihoods through trade and marketplace for thousands of years. Through our skills, creations, traditional knowledges, and artwork made from our own minds, hearts and hands. This resourcefulness is one of the key principles from our teachings of etuaptmumk. However, knowledge transfer and passing down of the intricate weavings our people are highly known for is decreasing in succession by each generation through the impacts of colonization and Residential Schools in Canada (Shubenacadie School, NS). Today, the number of weavers who carry knowledge of our traditional weaving techniques, known as jikji’j, is heavily endangered. The work of Francis, as a young weaver, alongside those esteemed and celebrated in our communities, is acknowledged as a staple to the preservation and revitalization of our cultural practices.

This is why, in 2018, the Canadian Space Agency sent Francis’ miniature baskets into space, marked a deeply historical and reverent moment for our culture and communities:

News story:

Miniature Basket from Eskasoni Goes Into Space with Canadian Astronaut

Canadian Astronaut Takes Mi’kmaw Basket to Space Station

In Johnson’s The Basket on the Moon (unpublished), I interpret her writing as a modern creation story or legend that remarks on the awe and wonder of space, the skills and gifts we carry as L’nuk, and most importantly, as being the creators of our futures, Intergenerational healing from my perspective (can’t speak on behalf of everyone), includes working on the self-esteem, cultural voice and pride of our people in connecting to our pasts through storytelling. Unfortunately, many of us have been left with contextual gaps in understanding due to the severity of what was lost. The story lights up my heart and soul, because it holds the same magic and supernatural forces we find in our older creation stories. Many old stories can read like prophecies and fated events, and this one, like the others, is no different. It’s increasingly important to see younger people in these positions in our communities.

Through the creation of this artwork, I carry the stories of my community on my back and inside the depictions of plants that are special to me, either culturally or personally (and both to be honest). Each plant in Nipniku’s is a story with an association to my family, chosen family, friends and elders. Plants on the left panel relate to the in-between realms, secret and closed knowledges of plant medicines that I hold close to me learned from helpers and people I’ve met along my path as well as learning how to identify, connect with, forage, protect and grow these medicines and plant allies on my own as I reconnect with the ecological practices of my community. These plants remind me of how I feel as a Two Spirit person, because learning and tending to these plant kin required a lot of patience, listening and observing of our roles and gifts in the natural cycles of life, how we weave through and mediate relationships between diverging perspectives, institutions, genders, individuals and networks. Our outsider and genderfluid gifts of walking a unique road, shows others how to integrate shadow parts of themselves and that we all want to belong and deserve love and acceptance. We offer a gift of insight and evoke compassion through our stories and experiences. However, two spirit medicine can sometimes be challenging to receive or understand by others. This is how some of the plants on this side of the mural are also understood. Some carry potent medicine that is to be used only by specific people at certain times, within cultural and social contexts and sometimes that makes them feared or avoided for “general use”.

Basket on the Moon, essentially is a piece about timing. Time-keeping of ecological cycles, timing of moments in history, timing of how we as people learn and take in things from our environment. June is a time of abundance, both for the city of Tkaronto, busy with festivals, patios and the boom of social life as well as the wildlife blooming of fruits, flowers, trees in this season. Everything comes alive and wants to communicate, talk to us, and we want to talk to everyone as well. Nipniku’s is a piece therefore about the “truth” part of Truth and Reconciliation, as a prayer put into creation to make us open to communicate from our hearts fully and with the best intentions.

The right panel of Nipniku’s features plants that are specific to the growing season of June, as well some of early Spring. This shows us how we keep a calendar of events that is honest and reflects an accurate account of protocol and what there is to do around us to be part of the greater whole. On a philosophical level, keeping accounts of the truth is similar. We cannot skip to reconciliation, but we can paint a picture of the ideal and build a vision for what could happen if we engage in restorative justice and accountable reconciliation processes.

The elements found on the bottom on Nipniku’s speak to the parts of this process that are operating under the surface, underground. Usually, we are not privy to what is beneath the Earth, what is growing, germinating, incubating or asleep. Under the ground, we see what is rooting and taking shape and rhizomatically shifting the collective consciousness. To be responsible and respectful, we may not be able to explain everything that is happening that cannot be physically seen, but I wanted to create visuals that do tell a story of things indeed taking place and the trust needed to let these emerge when they are ready to speak and reveal themselves. This is a spiritual process in itself, we all experience personal rites of passage at times in our life where we require to succumb to the unknown and release what we have no control over until we are brought to the other side of it.

Nipniku’s is rooted and grounded above everything else by my family: my mom, brother and grandmother and the journey we are taking together. Growing through life’s challenges, learning from one another’s personal ways of looking at things and blending together the specific purpose, reasons we were put together to meet in this life, as well as what we have to show and teach each other individually. This artwork comes from both artistic collaboration with them as well as through our love and determination to stay strong, strive and rise above our circumstances.

Emily Clairoux

Algonquin

@eaglewomanarts

Emily Clairoux is an artist from the Algonquin’s of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation, and is of mixed heritage Anishinaabe and French. She works under the name Eagle Woman Arts in her creative practice. Emily’s work is inspired by her community, as well as the teachings she’s picked up along the way. She grew up in a mixed family and has been impacted by colonialism and addictions. Learning to love herself has helped heal generational wounds, which is the foundation of her creative process. Emily studied at the Toronto School of Art and Centennial College in their Fine Arts Diploma Program and the

Community Worker Program at George Brown College. Emily says that her real education came from Finding myself through reclaiming my identity and learning about what it means to be Anishinaabe Kwe.

Mino Pimadiziwin – That Good Way this reminds many Indigenous peoples to walk in that good way or live in that good way.

Catherine Tammaro

Wyandot of Anderdon Nation

@Catherine.Tammaro

catherinetammaro.com

Catherine Tammaro is a multi-disciplinary artist whose practice spans decades. Catherine is a seated Wyandot FaithKeeper and is active throughout the City of Toronto and beyond in many organizations as Elder in Residence, Mentor, Teacher and Cultural Advisor. She is an alumna of the Ontario College of Art and has had a diverse career, multiple exhibits and installations, published written works, musical works, and presentations and continues her practice.

Catherine actively supports the work and development of other artists on an ongoing basis. She served on the Board of the Toronto Arts Council, TAC’s Income Precarity Working Group and was the Chair of the Toronto Arts Council’s Indigenous Advisory Committee in 2020/21. Tammaro is the Indigenous Arts Program Manager at Toronto Arts Council. She continues teaching, learning and exploring her creativity and that of others, held within our timeless connection to the sacred.

Aataentsic – Mother of Stories (Wyandot Version). SkyWoman is depicted here on the back of the Great Turtle, floating on the vast Primordial Sea, which reflects the cosmos. She is pregnant, a sunflower within her womb as she gives birth to life and seeds planted in the earth, Grandmother Toad brought from below. The Little Turtle, who lives in the SkyWorld, is visited by the little Deer, her loving friend... as she brings Spirits home.

Brandon Jacko

Anishinaabe

brandonjacko.com

@bjackoart

Based in Tkaronto, Brandon Jacko (Ojibway- Bear Clan) is an Anishinaabe Woodland artist from Wikwemikong, Manitoulin Island. Working with acrylic on canvas, he creates distinctive art that draws from contemporary themes while depicting stories inspired by his culture. Brandon began painting to connect with his heritage and encourage, protect and maintain Anishinaabe history and identity. His painting depicts stories and themes to share with his clients with bold colours, clean delicate lines and an articulate eye and a steady hand.

Brandon is a self-taught artist who draws his talent from innate ancestral abilities. His artwork has been obtained from art collectors all over North America and internationally as far as Australia and Paris.

Drumming Circle

Bees and Flowers

Ryan Besito

Anishinaabe

@besito.art

Ryan Besito is an Ojibway artist from Saugeen First Nations and has lived in Toronto for most of his life. Ryan’s art influence is inspired by Anishinaabe teachings and the wealth of street artists that also call Toronto home.

We The Nish – In each individual reside many stories. It is our inheritance and responsibility as Indigenous Peoples to breathe life into our stories every day.

Melissa Compton

L’nu/Scottish

@Comptons_creations

Melissa (Mel) Compton is a mixed urban Mi’kmaw/Scottish person living in Toronto. She is a multilateral artist who uses lived experience, artwork. Mel focuses on writing and therapeutic skills to develop and facilitate specialized youth programs within the urban setting. Blending creative processes with therapeutic practices, Mel strives to integrate the L’nu concept of ‘Two-eyed seeing’ into programs to provide an environment of skill development, positive identity and engagement.

Bead work that Melissa has beaded for community. Honoring the Plant Medicines her beadwork tells stories of Indigenous ways of knowing and being and the stories they hold.

Diversity and equity are top priorities at the TTC, and we are proud to play a role in acknowledging and celebrating the many cultures that make up our city each and every day.

Visit ttc.ca to learn more about our other diversity and inclusion initiatives.

Visit ttc.ca/jobs to learn about the TTC’s commitment to fostering a positive workplace culture with a workforce that is representative of the communities we serve.

Diversity Department

The TTC recognizes the importance of taking action to be responsive and reflective of the communities it serves, as well as to provide positive workplaces that value and support the full participation of all employees. To do so, while acknowledging a history of systemic racism and bias, the TTC is committed to implementing targeted initiatives to create an organizational culture of inclusiveness, respect and dignity that is free from all forms of harassment and discrimination. This will require “seeing differently, thinking differently, and doing work differently” (Racial Equity Tools, 2020), and the Diversity Department is here to provide leadership and guidance on how to do that.

Racial Equity Office

The Racial Equity Office (REO) is housed within the TTC’s Diversity Department. Through consultation and capacity building, the REO applies a racial equity lens to TTC policies, programs and initiatives to close opportunity gaps for Black, Indigenous and racialized communities. The REO also supports departments and business units across the TTC in promoting diversity, enhancing inclusion, and combatting racial discrimination in all its forms.

Racial equity is both an outcome and a process. “As an outcome, racial equity is achieved when race no longer determines one’s socioeconomic outcomes; when everyone has what they need to thrive, no matter where they live. As a process, racial equity is applied when those most impacted by structural racial inequity are meaningfully involved in the creation and implementation of the institutional policies and practices that impact their lives” (Race Forward, 2021).